Co-evolution

An essential activity that takes place in all kinds of things in the world.

In the past year, I realized that co-evolution is a common phenomenon in all kinds of scenarios. I think there are two reasons for such a realization. One is that co-evolution is a framework of interpreting things. When I look at things through this framework, everything becomes evidence that shows the framework is useful for understanding the world. The other is that co-evolution itself is an essential activity that takes place in all kinds of things in the world.

It doesn’t matter to me which reason is more correct. Looking back in history, we can see that the way things were interpreted was often part of the truth. We interpreted life as organic clockwork mechanisms in the 17th century, biological heat engines in the 19th century, information processors in the late 20th century, and complex systems in the 21st century. It turns out that life is all four.

So when it comes to choosing a way to interpret things, I think what’s more important is what kind of behavioral change such interpretation can bring to us. These discussions are covered more later in this article. But before that, I want to address examples of co-evolution in four different scenarios to provide a general feeling of what makes this concept powerful.

Society — Rules

In ancient times, humans were basically just another animal. We hunted, we ate, we had sex, we protected ourselves. Humans, however, were also social animals and tended to live and work together. In order to keep human society stable, we had to develop rules.

As human society grew larger, the rules also grew more sophisticated, and eventually became the laws and morals we knew. In such a process, it is not difficult to see that the rules were created by humans, and with the continuous evolution of human society’s structure, in order to maintain the stability of such structure, the rules also continued to evolve. The laws and morals of the past no longer apply to the present, and the laws and morals of the present will also not going to apply to the future.

In the other direction, the evolution of rules also changed the structure of human society and redefined what it means to be human. The structure of human society had grown as it is because rules provided constraints on how it could look. We no longer call ourselves animals because so many of the rules that distinguish us from animals have become part of our intuitive thinking.

Science — Engineering

According to Historian Yuval Noah Harari, science and engineering were two separate fields before the 17th century. It was after the 17th century when the two fields began to have a stronger influence toward each other. Nowadays, the development of the field of engineering depends heavily on our scientific knowledge. For example, we couldn’t have developed nanoscale microprocessors without knowledge of electromagnetism and quantum mechanics. The integration of science and engineering allowed the word “technology” to emerge and develop at an unprecedented speed.

On the other hand, the development of engineering had also greatly affected the progress of science. As Richard Hamming said, “Almost all of science includes some practical engineering to translate the abstractions into practice. Much of present science rests on engineering tools, and as time goes on, engineering seems to involve more and more of the science part.” For example, if we had not built hadron colliders, telescopes, and satellites, the development of particle physics, cosmology and earth science would have been greatly constrained. Not to mention that all the branches of science that depend on simulation in today’s world would not be growing so fast if we hadn’t invented computers.

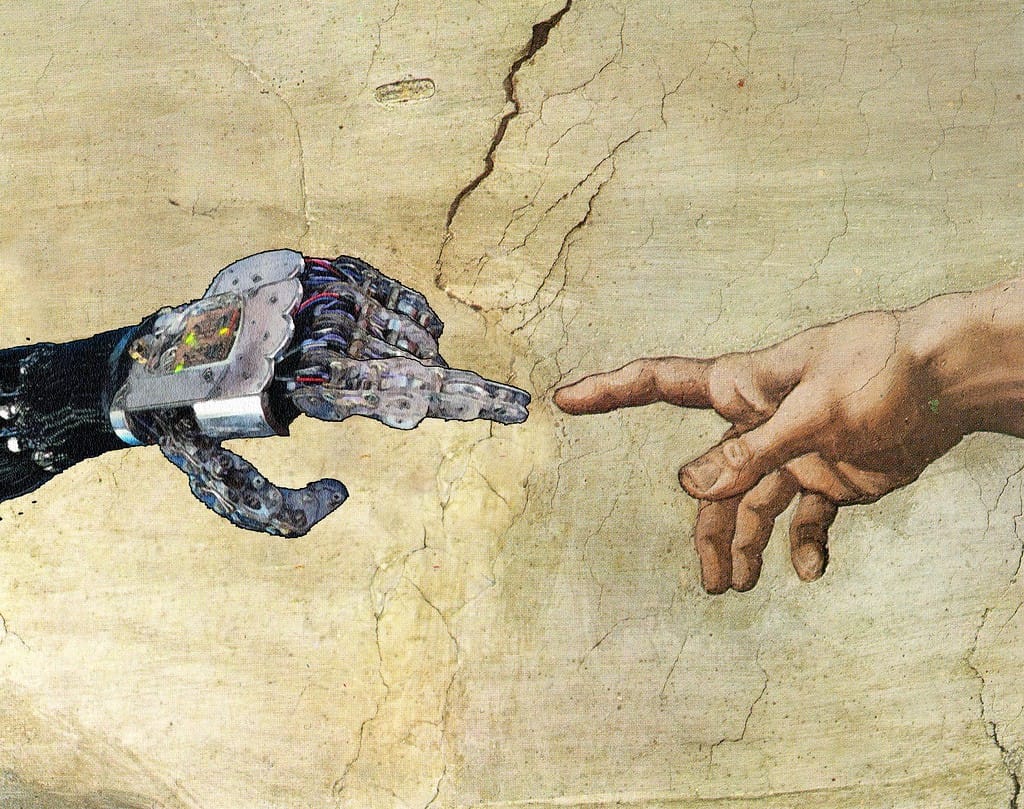

Humans — Tools

What happens between science and engineering can be discussed in a broader sense. In 1962, Douglas Engelbart provided a conceptual framework of treating the human system and tool system as an interacting whole in his famous paper Augmenting Human Intellect, which happened to be very similar to the idea J.C.R. Licklider proposed in his Man-Computer Symbiosis paper. The idea was that we humans create tools to enhance our ability to do things, but tools, in turn, also change human behavior. So when we create tools, we should not only think about how the tool can do what we want it to do but also think about how the tool can enhance human capabilities and change human behaviors.

A noteworthy example is Notion, a startup whose mission statement is: “We want to empower everyone to shape the tools that shape their lives,” in which their product is a digital workspace where you can organize information. I organized much of my information on Notion, and in using it over the past two years, I’ve found that my way of thinking has changed considerably. I became more able to use my brain resources for more important thinking. I was able to extract relevant information more quickly. The logic of the connections between my information became more explicit. What’s more important is, Notion provided me with a new way of manipulating information that can’t be done just with my brain.

In the other direction, the feedback from users like me has enabled Notion to continually improve its product. As my way of thinking has changed, so have my needs for the product, which eventually leads to a change in the overall design of the product.

Instinct — Principle

A few years ago, a friend of mine gave me the book Principles: Life and Work by Ray Dalio, which had a big impact on my life. After I read the book, I kept thinking about what principles I should set for myself. I looked at many examples, and then set a list of my principles and put them into different categories such as work, friendship, love, study, play, communicate, and so on. After I list these principles, I tried to live by them.

However, as time went by, I found that some principles did not apply to me, and I also found that I wanted to add some new ones, hence instead of acting 100% on principles, I tested them and adjusted them every once in a while. I also wanted to make sure that my whole system of principles is self-consistent, that two different principles should lead to the same behavioral decision for the same scenario.

To show how principles work, here I listed two of my principles under the category of “communicate.” The first one is “Don’t debate with people for the sake of winning or defending myself.” I’ve found that while trying to win a debate may give me some temporary pleasure, in the long run, it’s a waste of time that I could use to read a book, learn something new, or develop a skill. The second one is “Don’t try to impress others” because I realized the more time I spent on impressing others, the less time I spent on improving myself, and it’s more likely for me to result in having impostor syndrome.

As you can see, most of the principles were designed to limit some of my instincts, like the instinct to win a debate, the instinct to defend myself, the instinct to impress others, and so on. That is why I need principles, because by constraining these instincts through them, greater gains can be made in the long run.

What surprises me more, however, is not just how much gains these principles have given me, but how they have changed my instincts and personality. I have found that as I have practiced my principles, my instinct to debate, to defend myself, and to impress others has all significantly decreased. My perception of things has changed, my values have changed, my personality has changed. I no longer need certain principles because they have become my instinct. Not only am I renewing my principles, but my principles are changing me as a person.

Conclusion

After addressing examples of co-evolution in four different scenarios, now it’s time to answer the main question of this article: What kind of behavioral change can it bring to us?

We all know that things in the world change all the time, and by understanding the elements of co-evolution, we will have a more refined understanding of “how” things change, and it is only after we understand “how” that we have more ability to intervene.

Take doing things as an example:

If you want to do something, don’t just do it. Think about the co-evolution between you and the people around you. How might your action influence people? How might these people influence you in the future? What kind of culture might this action enhance? Don’t treat you as you and people as people. Treat you and people around you as an interacting whole.

If you want to do something, don’t just do it. Think about the co-evolution between humans and tools. What are some of the best tools to help you do it? Where can you get these tools? How might these tools change your behavior? Don’t treat you as you and tools as tools. Treat you and the tools as an interacting whole.

If you want to do something, don’t just do it. Think about how to set a principle that allows you to do it. Does this principle conflict with your other principles? If so, do you want to modify this principle or do you want to modify other principles? Or do you want to stop doing what you want to do? Don’t treat you as you and principles as principles. Treat you and your principles as an interacting whole.

Socrates said, “The unexamined life is not worth living.” I believe the concept of co-evolution is an excellent tool for examining your life.